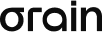

Lourdes Oñederra: "If silence is censorship or self-censorship, it condemns us to live without peace."

The absence runs through the lives of mother and daughter Elisa and Elixabete, the waves of the sudden loss strike their hearts relentlessly in the book Lastly (Erein, 2025), the third novel by writer Lourdes Oñederra (San Sebastian, 1958).

Elisa in San Sebastian and her daughter Elixabete in the United States, ghosts of the past appear to them when they look back, and they continually turn their eyes back on the work of 158 pages; now these ghosts are clouded by the awakened silence of the present and the future.

Oñederra is a writer and reference linguist (he is a full member of the Academy and has made an enormous contribution in phonetics and phonology) and has thus compiled a story about the consequences of violence and the burden of silence .

Where was he born ?What led you to the blank page and what guided you throughout the process?

As soon as I touch it, I fill the papers with words, drawings, schemes. I'm always aiming at things that I hear, that I can think of, that I can solve some problem that I have in my head, that I find interesting ideas, special pronouncements.

By the time I start writing a novel, I have already begun countless papers, chips, notes, sketches. Sometimes, as things get compacted, I start a notebook, or two, because I'm a little messy.

Elisa, Elixabete and, indirectly, Ixa are the main characters in the novel. How was the process of building their profiles and the way for them to face each other?

I wish I had clear ideas in this field, and I could answer clearly, but I don't. It seems like I start from people, from characters, making my way when I come up with a story.

I find it very difficult to invent, to develop the story, what is called the plot; these inventions go hand in hand, as they develop and develop. It's difficult for me, but that's also the reward I get when I write it: I get tired and suffer, but it also gives me a kind of pleasure, quite intense. I think that's why I write.

What's the relationship between the writer and the characters in the process of creating and writing the story?

In that sense, my relationship with the characters as writers is also sometimes tense, sometimes not so much, how to do it... Sometimes it can be up to identification, sometimes very distant, even despised.

These two extremes sometimes compress the writing, but they are also necessary for the assembly of the novel. After writing, things have happened to me with the previous novels, which seem to be happening to me something written.

The shadow of Ixa extends to the whole novel, but we are indirectly aware of that character who is the personification of evil.

I think the word you used, "shadow," is very appropriate. I think that's it, a shadow in the life of these two women. And yes, I will confess that I was tempted, that I probably had it before, because I find evil very attractive/exciting as a subject.

So I was tempted, tempted, but not attracted. I mean, starting with the evolution of the novel, I wasn't attracted to it, I didn't move the story. I think the backbone of the narrative was the two women, their insides, their relationship with each other.

For the time being, it is closer to the analytical aspect of evil than anything else that leads me to creation.

On the other hand, I don't know if I want to get into a man's head... I find it funny how there are so many writers who make women protagonists in their works.

It's a well-known subject, isn't it?

Absences and silence reign both in the worlds of the two protagonists and in the outside world which is represented in general.

It seems to me that silence sometimes protects us from the traps we make to ourselves; for in society it is too easily confused with differentiation, with harmony with the majority. If silence is censorship or self-censorship, I would say it condemns us to live without peace.

How do you write about silence and what's not?

Do I not know how to write about it, perhaps by writing it briefly, by putting it more into one's own notebooks than into one's own text, by the use of many ellipses, inexorably?

In the few conversations in the book you used an informal oral record (that is, det, aber, ginan, gendun...) and put the narrator in unified Basque.

When I answer this question, I am joined by the linguist and the writer.

Yes, as you say, I think the distinction is between conversation and the rest. To the extent that I have to "see" what I write, I even "hear" it in my mind as I write it, and it was not possible for those who were at that age to say "have" or "are" in the family environment in San Sebastian at that time.

To give just one example, we could take Margaret Atwood's book (The Robber Bride), mentioned in the novel itself, among many others, and see how it is perfectly normal for an informal level to appear in interviews (such as "How's it goin" and not "How is it going").

Now comes the linguist: Oral is not always informal. On the other hand, although I think that if the Basque language is going to go ahead, the Basque language is necessarily unified, we must not forget that the standard language is fed by other records of the same language.

After all, what do you wish for the book?

So he can get to somebody anyway.

You might like

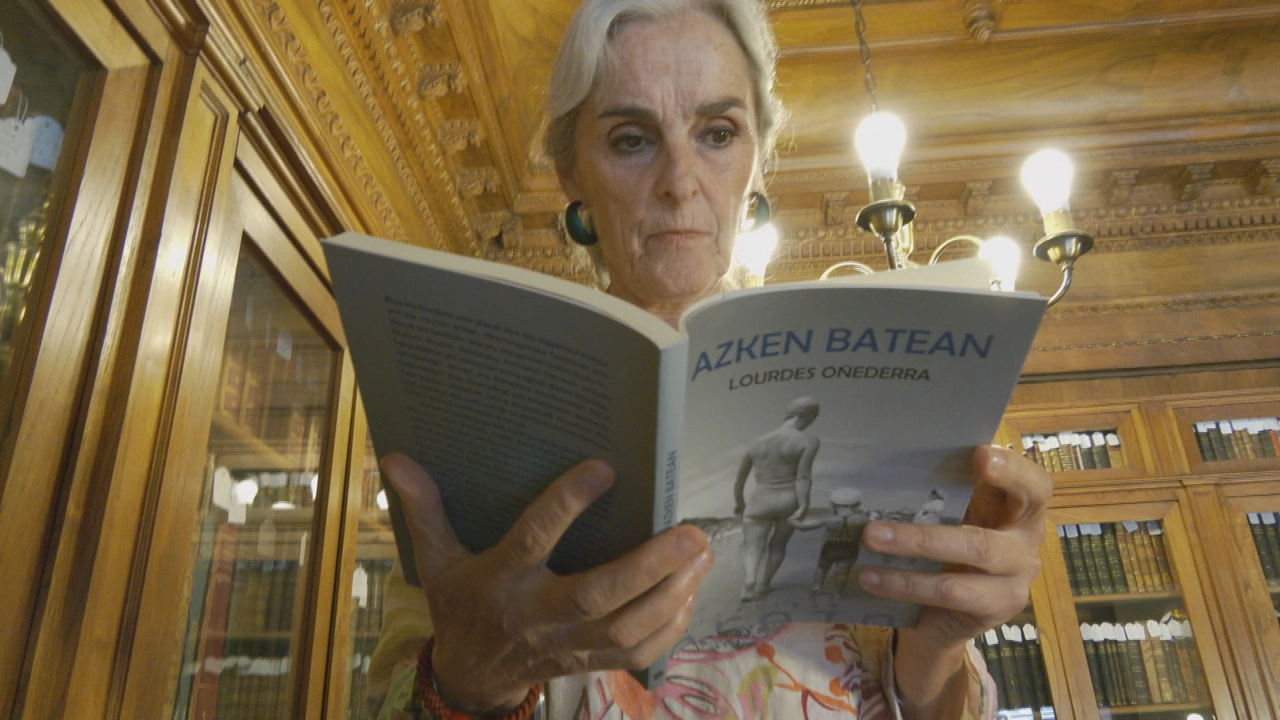

UPV and the University of Salamanca are studying the death of Miguel de Unamuno

How did the writer Miguel de Unamuno die? Did he have a natural death or was he killed? The debate about the death of the bilbaine writer has reopened and a study by the University of the Basque Country and the University of Salamanca seeks to clarify the fact.

UPV experts will participate in the working group to investigate Unamuno's death

A group of professors from various UPV/EHU departments have decided to promote an initiative to promote interdisciplinary research at the University of Salamanca. "The appearance of different signs of crime at Unamuno's house challenges the UPV to participate in the research that USAL has undertaken," they say.

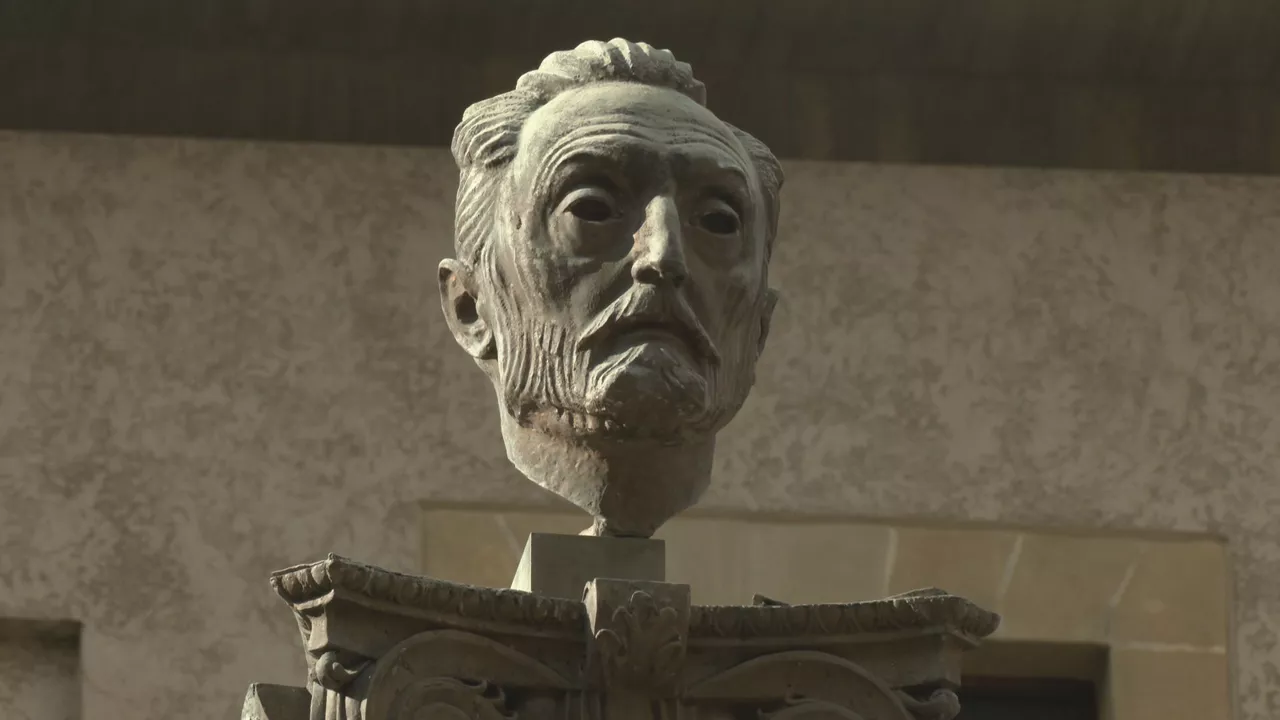

Joxe Azurmendi has been recognized on the last day of the Durango Fair

The members of the Jakin Foundation and Gerediaga have today paid tribute to Joxe Azurmendi, who has started from the latest issue of the magazine Jakin dedicated to the thinker, writer and Euskaltzale. Along with this, several poets have recited the late Manifesto ofAzurmendi on the last day of the Durango Fair.

The Basque Literature Awards have been awarded in San Sebastian

Although the names of the winners had already been announced, today, at the San Telmo Museum in San Sebastián, the Basque Country Literature Awards have been awarded. Seven awards have been awarded in as many sections. In Basque Literature, Unai Elorriaga has been awarded; in Spanish, Garazi Albizua.

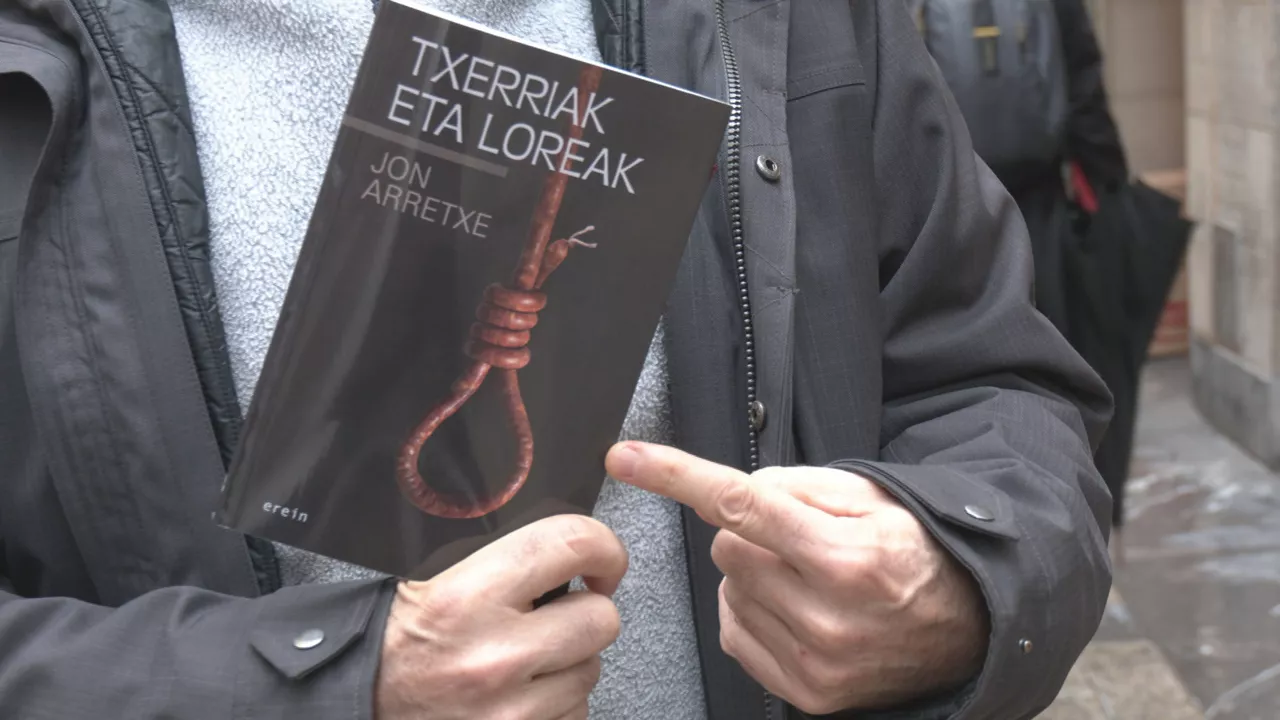

Jon Arretxe: "I felt the need to change."

Writer Jon Arretxe has set aside Touré's stories and published the black novel "Pigs and Flowers." It will be on sale at the Durango Fair.

Karmele Jaio: "I have made an intimate definition of reality"

The Vitorian writer presents the book Stone Heart , a work that collects all kinds of texts (reflections, memories, aphorisms, poems...) classified from A to Z or "a heartbeat alphabet."

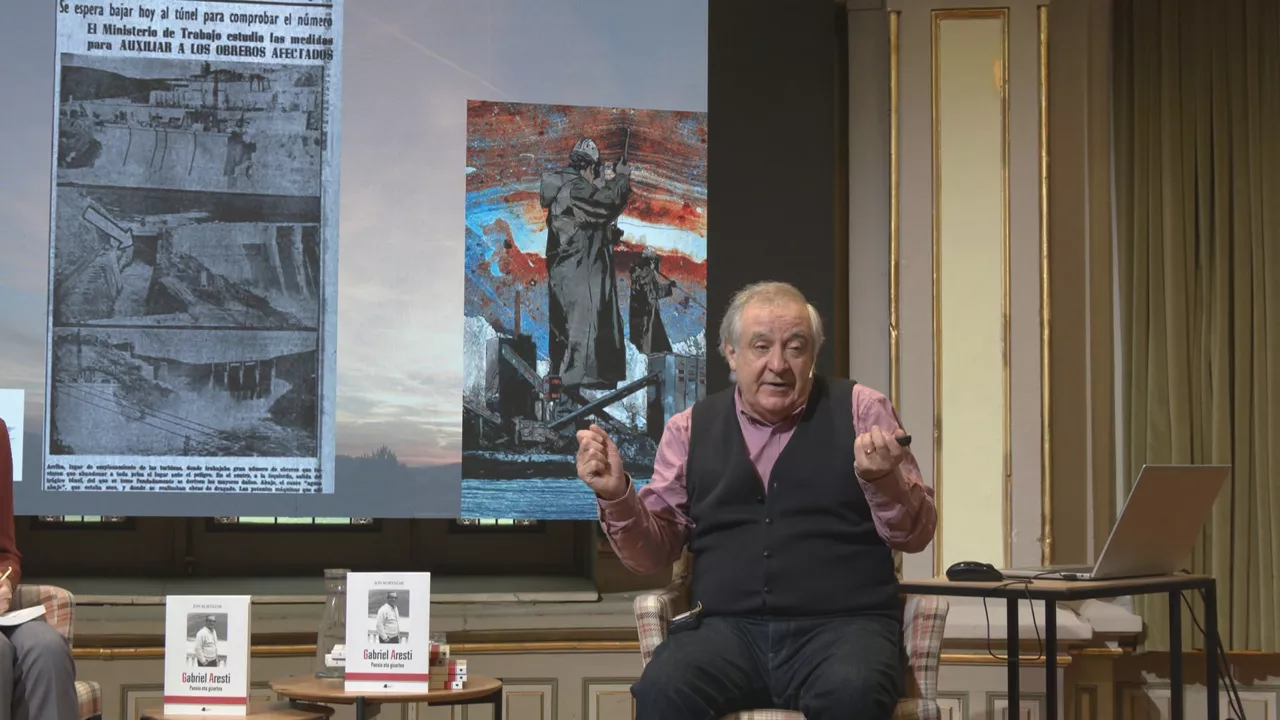

Jon Kortazar says, "Gabriel Aresti. He's written the book "Poetry and Society."

The professor and researcher has dedicated his new work to the poet in Bilbao (Pamiela, 2025), after publishing another book about Lauaxeta earlier this year.

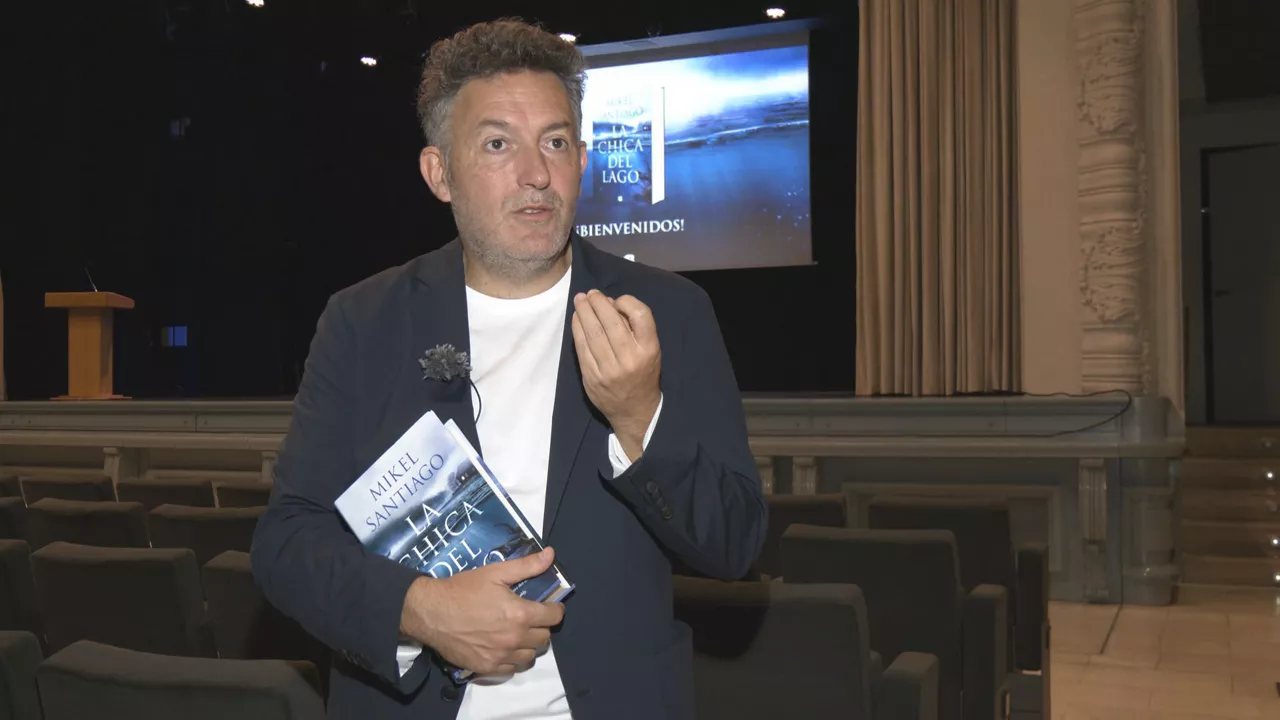

Mikel Santiago presents his novel "La chica del Lago" in Bilbao

The work is set in a small town in Álava. The writer has worked on general topics with the aim of reaching as many readers as possible. Many people have gathered at the book presentation ceremony and not all the people present have been able to access the room.

Idazleak, Garbriel Arestiren ispiluari begira

Ostiralean, azaroak 14, Edorta Jimenezek, Sonia Gonzalezek, Tere Irastorzak, Harkaitz Canok, Iñigo Astizek eta Leire Vargasek galdera honi erantzungo diote Euskaltzaindiaren Bilboko egoitzan: “Zer ikusten duzu Arestiren ispiluan zeure burua islatzen duzunean?”.

Bakardadea eta nortasuna hartuko ditu hizpide Literaktum letren jaialdiak

Donostiako literatura jaialdiak Juan Jose Millas, Eider Rodriguez, Javier CErcas, Lauda Chivite, Arantxa Urretabizkaia, Juan Manuel de Prada, Julen Apella, Belen Gopuegui. Harkaitz Cano eta Ignacio Martinez de Pison gonbidatu ditu, besteak beste.